Viewpoint

SICO’s Head of Investment Banking and Real Estate, Wissam Haddad, shares his thoughts on the recent trend of mergers in the GCC banking sector.

“Bank since 1472” reads the slogan of what is considered the world’s oldest surviving bank. Italy’s ‘Monte Dei Paschi Di Siena’ is a blend of hundreds of years of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) that have ensured its survival until today. Monte is not unique - similar M&As are what have made some of the largest banks today including HSBC and JP Morgan.

But why do banks merge?

Following a wave of global banking mergers in the 1990s, ten countries – referred to as the Group of Ten - including the US, Canada, Japan and others from Europe, set up a joint task force to study the impact of financial consolidation. The primary motives for consolidation stated in their 2001 report were cost savings and revenue enhancements. Information technology, deregulation, and globalization were also listed as factors encouraging consolidation.

The need for increased capital

Today, some 20 years later, the prime reasons for consolidation may be similar, but seem driven by the need for increased capital, required under the 2009 Basel III Accords following the events of the 2008 global financial crisis. These requirements oblige banks to have a certain amount of capital for each loan given out or each investment deployed, hindering growth especially for smaller banks with less access to capital. Stricter accounting rules have also meant that banks must estimate and provision for loans immediately on issuance which results in weaker capital, further stalling growth.

The global financial crisis had a major impact on global economic growth which, with some exception, seems to continue in our region until today, cuddled by trade wars, Brexit, volatile oil prices, global protests and increased protectionism. With more restricted capital, never-ending compliance costs, and slower economic growth, regional mergers today seem driven by the need for banks to enhance their capital base, reduce costs and enhance revenues (in lower or even negative growth environments) for survival. This stands in contrast with the global banking mergers of the 1990s, which were driven by profit growth and expansion, as well as the Dot Com frenzy. Today, regional banking consolidation may also be fueled by a race to the top, with larger local players looking to protect their turf and secure larger mandates in the face of increased competition from global players.

The benefits

Mergers, where two or more banks essentially become one, are expected to provide cost savings through staff redundancies, reduction in overlapping branch networks and combined back offices. Revenue enhancements are less vivid and stem from the larger client base of the merged entities and the cross-selling of services that may have been offered by one of the banks. Eliminating a competitor through a merger may also increase pricing power of the new combined entity. As an alternative to merging, banks have also increased capital by either issuing new shares– although this is less attractive for investors to buy into in periods of slow growth and lower profitability, or by issuing long term debt ‘bonds’ to buffer which have been attractive in recent years due to low interest rates, especially compared to the cost of equity.

The digital transformation

The threat to survival is not limited to capital and growth restrictions. Information technology, which was a factor highlighted in the 2001 Group of Ten report, has, once again, taken a front seat. Digital banking, open banking, and other financial technology (fintech) have ramped up pressure on banks to react or fossilize, with new regional digital banks (Meem, Ila, Jazeel in Bahrain, Liv in the UAE) launching and bank-nerving announcements by global giants Google, Amazon and Facebook of their own banking and currency platforms. Digital banks without any real estate, are expected to have significantly simpler customer engagement processes, lower costs, more personalization and wider customer reach. Open banking allows you to connect all your financial relationships (be it with one bank or more) and to compare and access competitor services from one app or website. Fintech covers all of these and more, shaking up everything from investing, insurance, fund raising, and banking.

In Bahrain, the launch of the so-called regulatory ‘sandbox’ in 2017 for fintech companies to setup and run their services in a protected environment with oversight from the Central Bank, has resulted in numerous participants launching from hotdesks at Bahrain’s Fintech Bay, which was also launched in early 2018. The Bahrain Investment Market, a quick-to-go-public share exchange platform initiative by the Bahrain Bourse, had its first listing of a fintech company earlier in December. Similar regional initiatives were also launched by all other GCC countries as well as Egypt and Jordan.

While GCC banks’ capital buffers are expected to remain resilient at between 12% and 16% of assets (risk weighted, as stated by Moody’s) in 2020, and reserves for bad loans at close to 100% in Bahrain and over 250% in Kuwait, the ongoing wave of mergers from 2009 in the GCC will also help buffer the expected increases in non-performing loans (projected by Moody’s at 6% of gross loans in Bahrain in 2020, compared to 3% for Oman, and 2.5% for Saudi Arabia). Non-performing loans, lower interest rates and their accompanying lower profit margins, and slower loan growth are all expected to further justify regional consolidation.

So, how do banks merge?

In Bahrain most banks are listed on the Bahrain Bourse with mergers regulated by the Central Bank’s Takeovers, Mergers and Acquisitions (TMA) rulebook. Furthermore, Bahrain’s Commercial Companies Law (CCL) codifies additional requirements for all mergers. In general, the TMA heavily democratizes the process, seeking to protect minority investors with detailed transparency requirements, equal offers to all, and change of control safeguards with a 30% ownership threshold. While mergers of unlisted entities can be affected by a shareholder majority at an extra-ordinary general assembly, listed banks additionally need to appoint a slew of third party advisors and issue detailed offer documents and independent advisory reports to fully inform investors of their options, risks, timelines, results, and processes under the active watch, regulation, and approval of the Central Bank.

The acquiring bank would normally pay for the merger in one or a combination of: i) issuing more of its own shares and exchanging those new shares with the shares held by shareholders of the target bank; ii) creating a new overhanging legal company into which the merging entities are rolled up, with all merging entity shareholders receiving new shares in the holding entity; or iii) straight cash payments to the target shareholders. While it seems that the acquiring bank paying for its target using its own newly issued shares is a ‘cheap’ way to do so, as no cash is involved – this is completely false. When a bank issues new shares paid to the target’s shareholders in a merger, this bank’s ‘original’ shareholders now own that much less of it and that much less (as a percentage) of any profits or dividends paid out.

Accordingly, a merger of any kind assesses the impact on earnings per share (EPS) both before and after the issuance of any new shares used for an acquisition and the impact of any financial benefits from such a merger (revenue enhancements / cost savings etc.). If EPS is lower after the merger, this is deemed to be a dilutive merger and therefore unfavorable to the acquirer’s shareholders, while higher EPS results in an accretive and financial favorable merger for the buyers. A whole range of non-financial metrics further complicate success and failure, including corporate cultural differences, staff redundancies, integration, antitrust issues, legacy systems, and Shari’ah versus conventional banking, among others.

The GCC wave of M&As

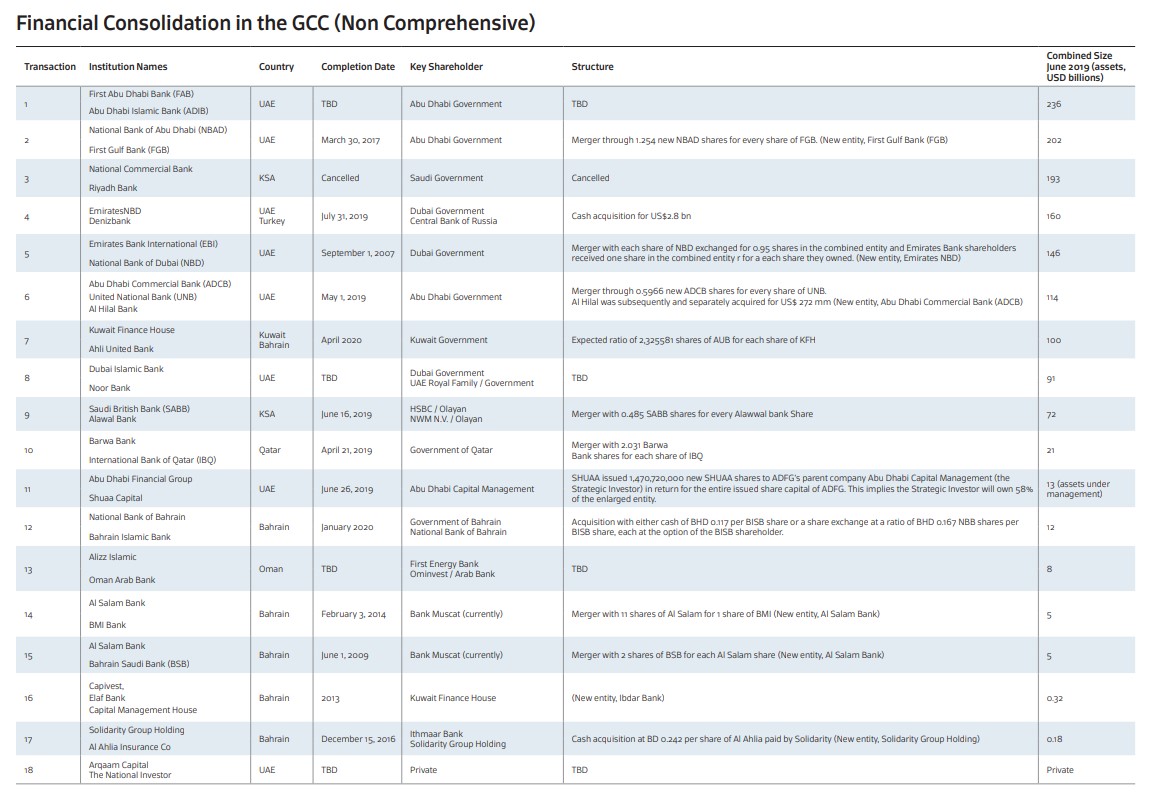

So far in the region, a majority of the more than two dozen recent banking mergers have had some common shareholding across the merging entities, which simplified the generally complex decision-making and implementation process. Notably among recent transactions, is the merger of First Abu Dhabi Bank and Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank, with over US$ 230 billion in assets. Currently, two separate mergers/acquisitions are underway in Bahrain’s banking sector, expected to be completed in early 2020, including a cross-border transaction. First, is the acquisition of Bahrain Islamic Bank by National Bank of Bahrain, which was concluded on January 22nd and is considered to be the largest M&A transaction in recent history.

Second, is Kuwait Finance House and Ahli United Bank, which will see the latter become a fully digital bank, as directed by the Central Bank of Kuwait. The transaction received approval from shareholders at the end of January 2020. Other mergers are expected to follow, while some may not follow through – initial merger discussions between Saudi’s National Commercial Bank and Riyadh Bank were officially called off in December 2019 without a stated reason.

Going forward, M&A in banking, since 1472 and even earlier, will continue to be a fundamental growth and survival mechanism. It is expected to further blur the lines between finance and technology, with banks acquiring fintech companies and tech companies taking over banks.